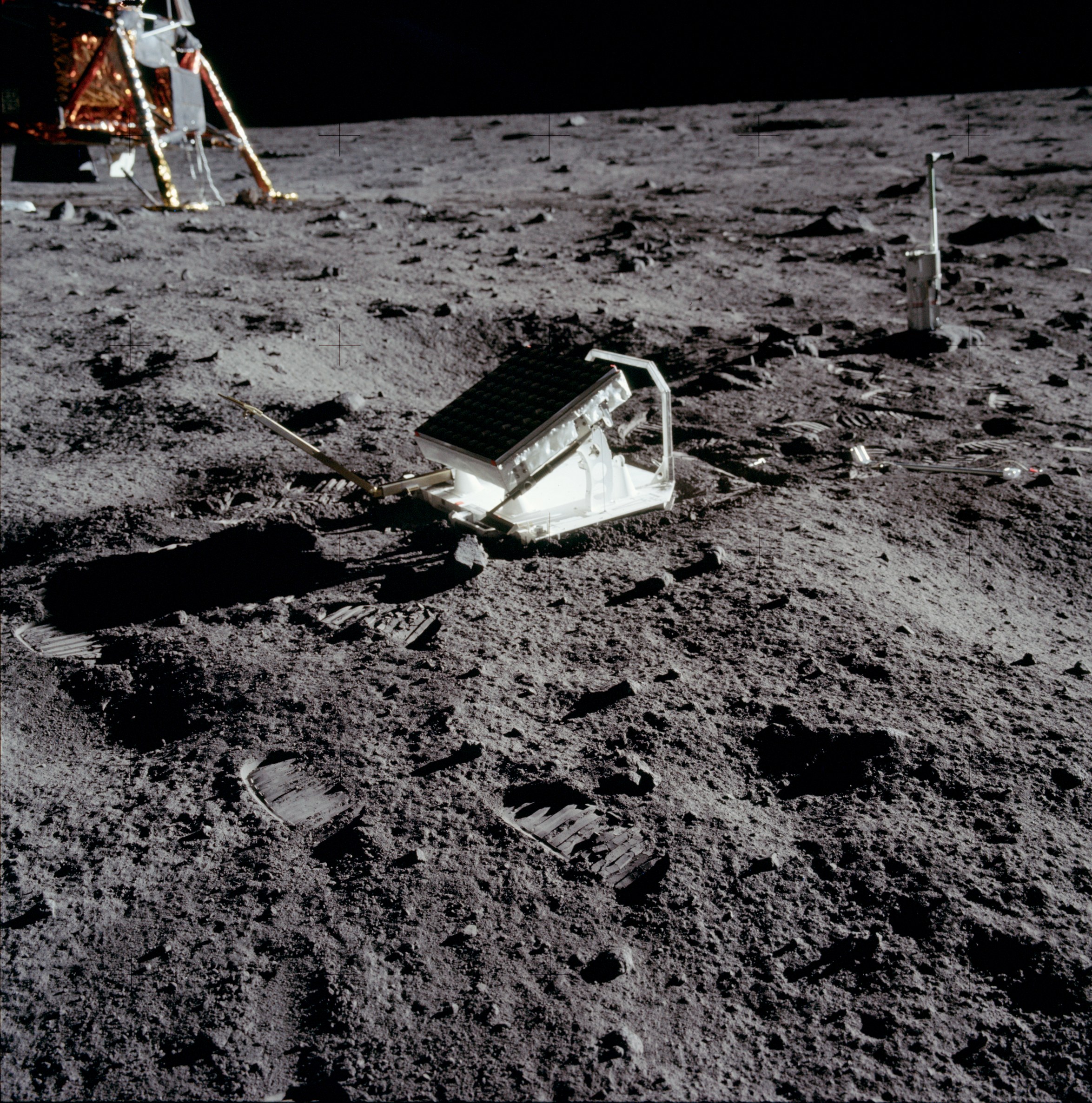

Fifty years ago Apollo 11 not only landed on earth’s closest celestial body but left behind equipment that allows an incredibly precise measurement of the Moon’s distance.

The giant leap for mankind allowed researchers to used a 120-inch Shane Telescope to fire a powerful KORAD K-1500 Ruby Laser at the moon and detect the light that bounced back from a retro-reflector array placed on the lunar surface.

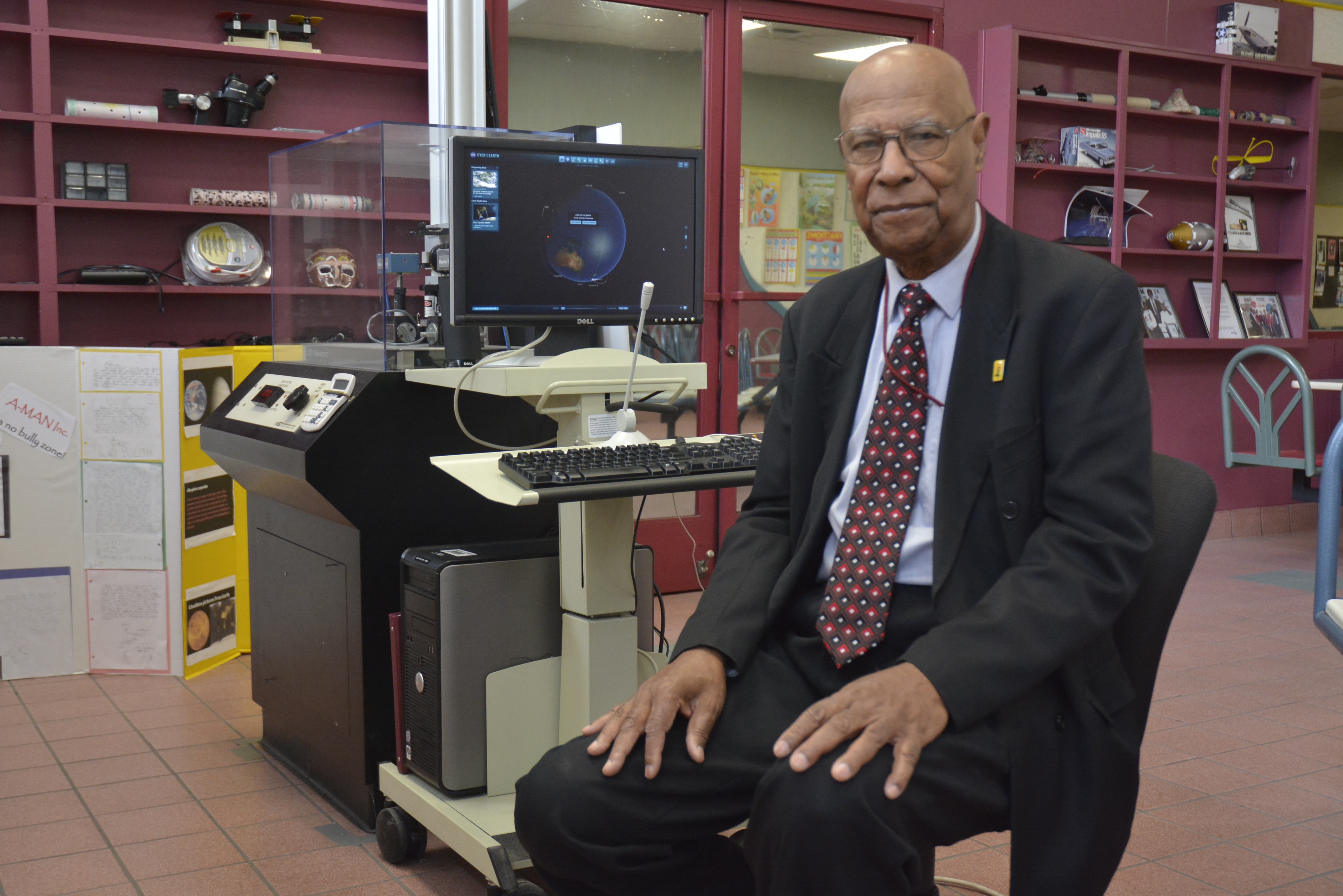

No one is as gratified as Hildreth “Hal” Walker, Jr. His accomplishment is an overlooked — and crucial — contribution to a pivotal moment in American history.

“It was a lonely period as a black scientist in those days, especially a laser scientist,” says Hal.

He joined the team of scientists and students at the University of California’s Lick Observatory in 1969 and was responsible for maintaining the the Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment (LURE).

The team overcame numerous technological challenges to get the LURE to work. While locating the target was no easy task, luck may have been a factor.

The Lick Observatory initially encountered difficulties because Apollo 11 touched down miles off-course from its expected landing site.

“We start operations on July 21,1969 and found the reflector on August 1, 1969,” recalls the 86 year old Hal.

Accord to Hal the moon was only available about 45 minutes each day due to its low position on the horizon. Also pulse lasers weren’t designed to run continuously and take so many shots.

As the other sites battled technical problems scientific ingenuity and pfatiences enabled Hal to maximized his laser’s performance.

The laser was powerful, about 3 times brighter than the sun. It took Korad Corporation six months to build the working unit.

The team at Lick Observatory were not alone in their quest to locate the lunar array. Numerous laser sites across this planet were also in the search.

Prior to the Apollo 11 mission that took the laser reflector to the moon, distance measurements between earth and its closest celestial body was compile using radar. The error factor was a quarter of a mile. Today that measurement is a single millimeter.

Like many black scientist and technicians who have make significant contributions to science, Hal has overcome racial adversities too.

In a 1970 Scientific American article titled “The Liar Laser Reflector” Hal’s name was omitted from the Lick Observatory team roster. Hal was understandably angry. He called a team member to complain. According to Hal his team member’s response was “there wasn’t enough room to mention your name.”

Hal, a New Orleans native, has been involved in aerospace for more than 50 years. His meaningful contributions has lead to a stellar career in science and education.

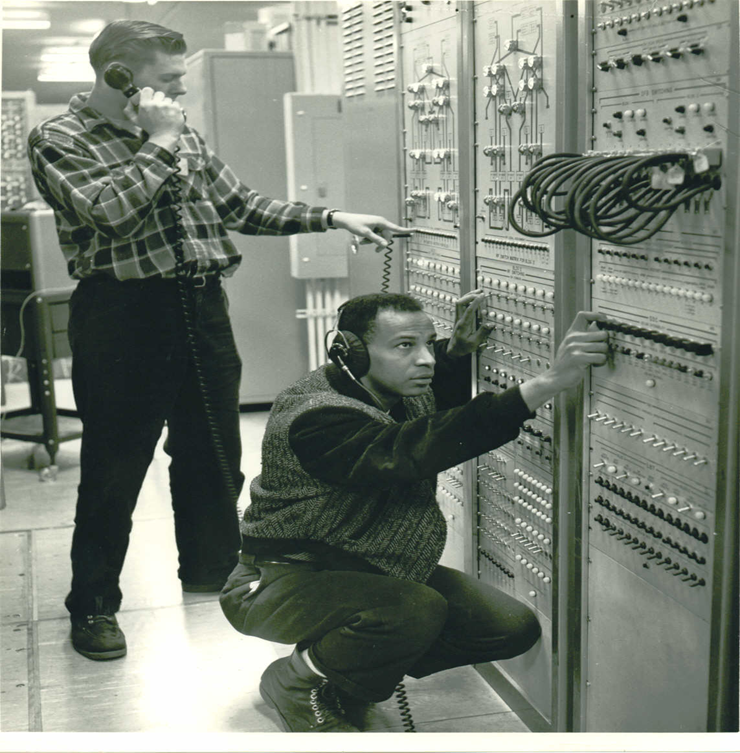

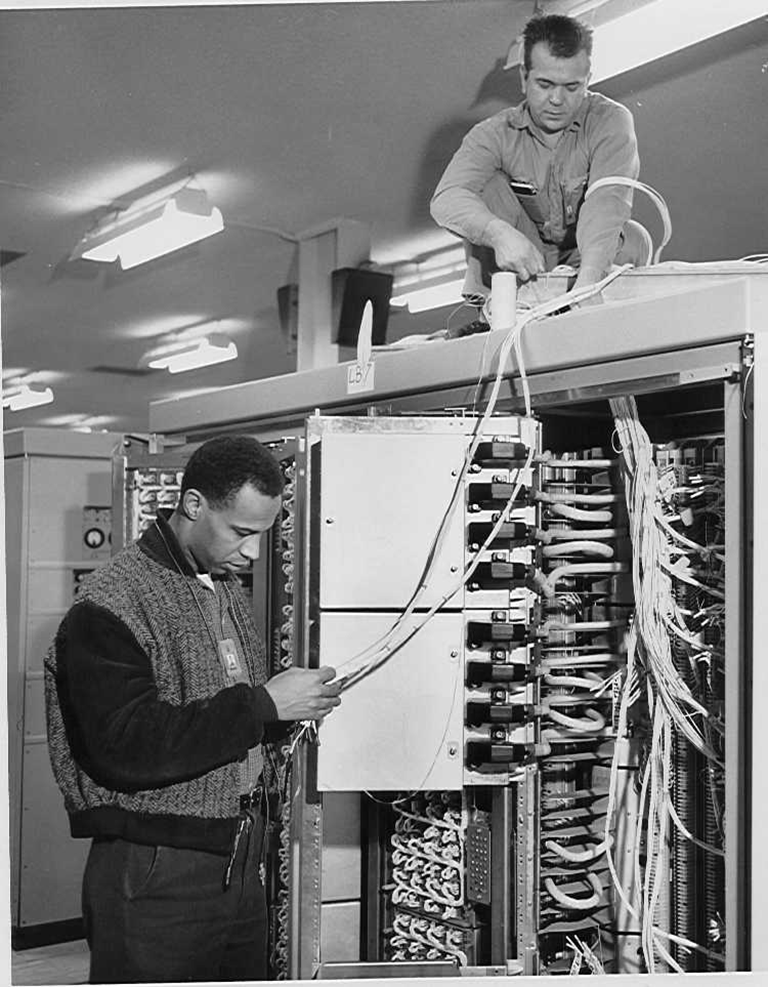

Years prior to his lunar laser project he was recruited to participate in a classified project titled the “ballistic missile early warning system,” at Bear Air Force base Alaska from (1959-1960). It was this country’s first early warning system against a nuclear attack.

Five black field engineers among 1500 civilian workers including two from RCA and three from General Electric. They worked 10 hours a day, seven days a week for one year.

Hal admits working the highly classified military project was the best thing to ever happen at that time because he learned about radars and power systems. Credentials that made him a valuable asset to the Korad Corporation.

After a successful career with Korad he understood the importance to recruit blacks into the field of science and technology.

For several decades he continues to bring science and technology to the forefront of the African American community.

“It’s important that we of African heritage be seen as part of the expansion of humanity into space,”said Hal.

Hal along with his wife Dr. Bettye Walker form the African American Male Achievers Network (A-MAN). For 25 years this organization has work with K through 12 students including females.

According to Dr. Walker the program has graduated over 10 thousand students for colleges and universities in the United States and South Africa.

“This program is incredible,” said Dr. Walker. Early intervention makes a difference.

The curiosity of these young minds are stimulated through hands-on activities without sophisticated equipment.

Hal recalls recovering devices other organizations had throned away and bring them to the “Take Apart Lab” where students disassembled the equipment to learn how it works.

During a 1997 visit to South Africa, Hal and Dr. Walker accompanied by a group of 8 to 12 years old students, met President Nelson Mandela.

Enamored by the students passion about their involvement in science and technology President Mandela cancelled his next appointment to spend an additional 90 minutes with the students.

He asked Hal and Bettye to create a science and technology program for South African students.

“President Mandela saw those A-MAN youngsters as a model of what can be done with the youth of South Africa to build the next technological generation of South Africans,” says Hal.

A-MAN is affiliated with over 20 sites in South Africa including schools in the Pretoria, Johannesburg and Cape Town as well as Los Angeles CA.